alan little’s weblog

chariots and the age of the rig veda

20th August 2003 permanent link

I’ve written a fairly long piece about the military significance of chariots in the Bronze Age, and why I think the earliest Hindu scripture, the Rig Veda, can’t have been composed much earlier than about 1500 BC. Why? I first came to this subject through my interest in yoga, specifically through reading in Georg Feuerstein’s The Yoga Tradition that the Rig Vedas - the earliest Hindu sculpture and therefore in a sense the root of yoga philosophy - might be far older than western scholars generally used to believe.

I started doing some reading on the subject and discovered that this is a hotly controversial subject in Indian history, bound up with Indian nationalist backlash against British imperialism and with all kinds of domestic political agendas. I find this both fascinating and rather depressing - I’m a retired historian myself (i.e. did a PhD in history before realising that the prospects of actually being able to make a living were better in software) and I still have an interest in looking at controversial historical topics like this and wondering whether there’s any chance of anything other than rival tribes shouting ideology & speculation at each other. There are some people in the field who are genuinely interested in trying to get at what might actually have happened based on the very sketchy evidence available, but are they ever going to be the loudest voices? Probably not.

I will have more to say on this subject but meanwhile, here are my thoughts on what I think is one of the clearest and most obvious reasons why the Vedas can’t be much older than European scholars originally thought.

The Vedic heroes are chariot-riding archers. This single undisputed fact tells us a lot about both the nature and the date of their society. It means that the Vedas - at least the parts that describe chariot warfare and rituals to do with horses - can’t be much older than about 1500 BC. But it also means that the Aryans were living in a sophisticated technological civilization and weren’t a nomadic barbarian horde.

robert drews on chariots and the bronze age kingdoms

American classicist Robert Drews, in two books, outlines his theory that the rise and fall of the the rise and fall of major Bronze Age civilizations in Greece and the Middle East in the second millennium BC can largely be explained by the history of the war chariot as the ultimate weapon of the ancient world.

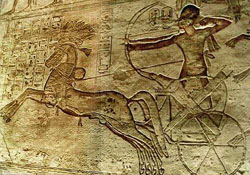

Summarising very briefly, based on archaeological and linguistic evidence he believes that the war chariot was invented and first put to effective use by people speaking Indo-European and related languages, probably somewhere in Eastern Anatolia / the southern Caucasus, around 1800 to 1600 BC. Circa 1600 Troy and the Hittite empire were founded in Anatolia, Mycenae and other city states arose in Greece, and Minoan Crete was conquered by Greek-speaking rulers from the mainland (other historians question how useful chariots would have been in the mountainous terrain of Greece, and I find it it hard to see how they would have been relevant to a seaborne invasion of Crete). Egypt was briefly conquered by the Hyksos, a group of chariot warriors from the north at least some of whom were Indo-European speakers. In order to fight back successfully against the invaders the Egyptians themselves had to adopt the chariot; and it remained the military basis of the power of the New Kingdom pharaohs, the most famous of whom was Ramses II. Numerous other kingdoms in the Levant and Mesopotamia appear to have been ruled for some time by Indo-European speaking chariot warriors.

Ramses II

Drews assumes that the arrival of the Sanskrit-speaking Vedic people in India was part of this wave of military/political takeovers of already existing civilizations, and speculates that they could have arrived by sea from Mesopotamia rather than overland.

the chariot as the ultimate weapon of the bronze age

technology

The chariot was a complex, expensive, high technology and high maintenance weapon system. Chariot armies required a wide range of professional specialists to build, maintain and fight - chariot-makers, bow-makers, horse breeders and trainers, drivers, archers, scribes who kept detailed records of the royal chariot fleets. According to Linear B tablets from Greece and Crete, royal armies seem to have kept more spare parts in stock than actual operational chariots - a good indication that they were a valuable but fragile piece of state-of-the-art technology. In terms of their cost and technical sophistication relative to the societies that used them, they could perhaps be likened to modern jet fighters.

Maintaining a chariot army also assumes trade links over a wide area - chariots were built from temperate forest hardwoods, but were only of military relevance on open plains and were used in places far away fom any temperate hardwood forests. Birch bark, for example, was used to lash the spokes to the rims of Egyptian chariot wheels; and Ramses II wasn’t growing many birch trees in Egypt. The horse wasn’t native to the chariot kingdoms either; the best horses came from Armenia and were traded all over the Middle East. Bronze weapons also required trade over vast distances - the tin used to make bronze in the Eastern Mediterrannean came from mines hundreds of miles away in Sardinia, or even Cornwall.

psychology

There is a fascinating book by on the psychology of warfare by Dave Grossman which offers a number of explanations of why the chariot was such a devastating weapon.

Grossman is a former American special forces officer turned psychologist. He has a fundamentally optimistic view of human nature: he believes that, like nearly all mammals, humans have a strong innate reluctance to kill one another. Primitive tribal warfare in his view is largely aggressive posturing, and much less lethal than it looks. This continues into modern times - as late as the second world war, there is lots of evidence that most soldiers in battle are reluctant to shoot at the enemy and most of the killing is done by a small minority. Grossman maintains that for most people, the psychological stress of having to kill other people in war is actually stronger than the fear of being killed.

One of the fundamental things armies have learned over the centuries, then, is a range of tools and techniques for overcoming the average soldier’s natural reluctance. Grossman’s main interest in this is that he believes these techniques have become far more psychologically sophisticated and effective since the second world war, to the point where they pose a serious danger to modern society. Maybe. But he also discusses how they have evolved over the entire history of warfare, and several of them are relevant to why chariots might have been so effective:

- Soldiers are more likely to kill fighting in close teams than fighting alone. In modern warfare, machine gun and artillery crews don’t show the same unwillingness to fire effectively as individual riflemen do - reluctance to let the team down partly overcomes reluctance to kill. Chariot soldiers fought in pairs, driver and archer. And the most famous description of a chariot team in all of history and literature is, of course, Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita convincing Arjuna to fight at Kurukshetra.

Krishna & Arjuna - It is psychologically easier to kill at a distance than close up. The chariot team’s main weapon was a composite bow with an effective range of 70 metres or more.

- It is psychologically easier for soldiers to kill people they percieve as socially, culturally, linguistically (’racially’ if you like that basically meaningless word) different from themselves. Hence why modern societies in wartime put so much effort into propaganda that demonises and dehumanises the enemy. Chariot warfare seems to have been an ’Aryan’ / Indo-European invention that enabled foreign warrior aristocracies to conquer and - at least for a while - displace the native rulers of settled kingdoms. Even after the native elites in places like Egypt copied the invaders and fought back, chariot warfare was still carried out by a privileged professional warrior caste who lived lives very different from most of the population.

- A small percentage of the population seem to be ’natural soldiers’ who lack the normal innate reluctance to kill. Small professional armies can pick out and train a higher proportion of these people than mass conscript armies. Chariot armies were small professional armies.

the end of the bronze age

According to Drews’ theory, chariots were the basis of the military power of late Bronze Age kingdoms for several centuries. Around 1200 BC, though, Bronze Age kingdoms collapsed all over the Eastern Mediterranean world. He cites archaeological evidence of almost 50 major cities that were destroyed within a few decades including Troy, Mycenae, Knossos and the Hittite capital of Hattusas. The longest established civilizations in Egypt and Mesopotamia survived, but the golden age of the pharaohs was over. Elsewhere, there was a ’dark age’ lasting several centuries until the rise of iron age civilizations such as pre-classical Greece. Why the collapse? Drews discusses a number of theories that have been put forward:

Invasions by migrating barbarian hordes from the north. Indo-European speaking migrating Aryan hordes were a favourite fantasy of European nationalist historians in the nineteenth century - but there simply isn’t much evidence for them, either in India or the Middle East. What archaeological evidence there is for the post-collapse world shows no sign of the existing populations having been displaced by invaders with a different culture. It does suggest that the surviving populations were living in a world with much lower levels of wealth, safety and political stability.

Destruction by massive acts of god - earthquakes or volcanic eruptions. This one is a favourite among pop historians and the general public - but again, the evidence doesn’t fit. The damage to the cities that were destroyed isn’t consistent with earthquake damage; it is consistent with them having been sacked and burned in wars. Some of the famous cities that were destroyed - Knossos, Mycenae, Troy - were in earthquake zones, but lots weren’t. And there is no evidence from any period of known history of earthquakes so devastating that they end civilizations. Cities get destroyed, but the survivors rebuild them and carry on much as they did before.

’Systems collapse’ - the Bronze Age kingdoms collapse under the weight of their own internal social/economic failings. Drought, or famine, or shortage of tin to make bronze; over-dependence of the palace elites on international trade in a few valuable commodities; risings of oppressed peasants against their (often foreign) rulers. These ideas have been favourites among Marxist-influenced writers since the British historian Gordon Childe in the 1940s - but Drews sees little actual evidence for them. They don’t explain the sudden destruction of cities: why would an unarmed and downtrodden peasantry suddenly be able to overthrow kingdoms with professional armies that had successfully oppressed them for hundreds of years? And they don’t explain why, as far as we can see from the written evidence, the royal administrations were functioning smoothly right up to the day the cities burned.

Drews’ own theory is that the kingdoms were overthrown, not by their own oppressed peasants or by invading hordes from far away, but by soldiers from semi-barbaric territories on the fringes of the civilized world who had previously been employed as mercenaries in the royal armies. He points to archaeological evidence that armour suitable for light, mobile infantry started to be widely made and used around this time; effective swords were first invented in Italy and the Balkans and were soon copied in Greece and the rest of the civilized world; and javelins seem to have been far more commonly used as a military weapon than they ever were before or since. Putting all this together, he believes that light infantry had been employed all along by the chariot armies, as skirmishers and support for the chariots. These soldiers were mostly foreign mercenaries, not natives of the kingdoms. The kingdoms were ruled by tiny elites, some of them foreign to the populations they ruled, who certainly would not have wanted their peasants to have effective weapons and military training; barbarian boys from the hills were also fitter and tougher than peasants from the river valleys. Some time around 1200 BC, helped by improved weapons and armour - javelins to bring down the horses, armour and swords to fight the crews - the mercenaries realised that they could beat the chariots and loot the wealth of the kingdoms. The rule of the kings and their chariot warriors was over.

but what does any of this have to do with india and the vedas?

dating the vedas

There is no evidence of lightweight chariots existing anywhere in the world before about 2000 BC at the earliest. There is no evidence of war chariots having been of great military significance before about 1650 BC. In India, archaeological evidence of horses existing at all before about 1500 BC is at best sketchy and controversial. Anybody who believes in a date much earlier than circa 1500 BC for the Vedas (and some have suggested dates earlier than 4000 BC) therefore has a big job to do explaining away chariots. Some possible explanations could be:

- Chariots did in fact exist, and were the ultimate weapon system, in India hundreds or even thousands of years before they were known in the rest of the civilised world - but they left no archaeological evidence, and nobody anywhere else heard of them or managed to copy them, even though there were undoubtedly trade and cultural links between the Indus Valley civilization in India (circa 2700 to 1800 BC) and Mesopotamia. Which seems highly unlikely.

- Some parts of the Veda are, indeed, much older but the parts describing chariot warfare are later additions. This isn’t completely out of the question - an obvious parallel would be, for example, Mediaeval European paintings of the Trojan War or classical battles, where ancient Greeks and Romans were often shown with Mediaeval European-style armour and weapons. Either the artists had no historical sense of things having been much different in the past, or they just showed what they thought their patrons expected to see. The people who put the Vedas into their final form could have grafted anachronistic descriptions of warfare and horse sacrifices onto much older material. This is perhaps possible, but doesn’t seem at all likely - all commentators on the Vedas appear to regard horses and chariots as absolutely central to Vedic culture, not something that could easily have been added later.

- Chariot warfare arose in India about the same time as it did in the rest of the civilized world and probably in the same way - brought by a relatively small conquering army of Indo-European speaking chariot warriors who orginally came from somewhere in the Middle East, probably eastern Anatolia. In other words, the chariots in the Vedas strongly suggest that there was some kind of ’Aryan Invasion’, although it was not anything like the migrating barbarian horde that nineteenth century European nationalists dreamt up.

vedic society

What can we infer from all this about the nature of Vedic society? Who are the Aryan heroes?

If they are charioteers, they cannot possibly be semi-barbaric pastoral nomads. They are a professional warrior elite in a sophisticated society that can support a wide range of specialised professional skills, long-distance trade and complex technology.

They might well have been a distinct linguistic and cultural group within their society. According to Drews there is lots of evidence from the Near East that civilized Bronze Age societies were multi-lingual and multi-cultural, not the homogenous ’racial’ units of nineteenth and early twentieth century European nationalist fantasies. There is also evidence - for example from widespread borrowings of Indo-European horse and chariot words in other languages - that within these mixed societies, Indo-Europeans had a traditional role and reputation as horse trainers and chariot soldiers. Drews cites several examples of societies where people with Indo-European names lived alongside people with non-Indo-European names, and the Indo-Europeans appear to be disporoportionately concentrated in the court and the military.

The Vedic Aryans have a common cultural heritage with western Indo-Europeans that must have diverged after the chariot became an important part of the culture, i.e. after about 1900 to 1800 BC at the earliest, more likely after around 1600 BC. Vedic, Roman, Greek and Celtic culture have very similar rituals and myths involving chariot horses and ’heavenly twins’ who may well have originated as driver-and-archer chariot teams.

Even if Sanskrit-speaking Aryans brought the chariot to India, and became a dominant warrior elite as a result, this does not means that they were an invading horde that displaced the native population. They could equally well have been a small group of professional soldiers who started off as mercenaries serving an existing ruling elite, until eventually they built up the confidence to overthrow it and take power themselves. There are lots of historical examples of that sort of thing happening - see for example the entire later Roman Empire; and mediaeval Islam from Saladin in the Crusades, to the rise of the Ottomans.

references

On the rise and fall of the chariot as the ultimate weapon in the Eastern Mediterrannean and the Near East and its political and social implications, my main source is two interesting books by Robert Drews:

The Coming of the Greeks - Indo-European Conquests in the Aegean and Near East, 1988. ISBN 0-691-02951-2

The End of the Bronze Age - changes in warfare and the catastrophe ca. 1200B.C., 1993. ISBN 0-691-02591-6

Dave Grossman’s book is:

On Killing - the psychological cost of learning to kill in war and society, 1996. ISBN 0-316-33011-6

update

2nd January 2004

“There is no evidence of lightweight chariots existing anywhere in the world before about 2000 BC at the earliest”. Oops. Yes there is. Whilst reading up on a new theory about the origins of of the Indo-European languages, I came across references to discoveries in the mid-1990s of chariots in an area called Sintashta-Petrovka in the southern Urals, dated to 2100 BC. See particularly this sci.archaeology posting by S.M. Stirling. Apparently they are of a design similar to later Middle Eastern war chariots, although less advanced (e.g. narrower wheelbase, so less stable). This is interesting.

- It clearly seriously damages Robert Drews’ theory (1980s, predating these finds) that the Greeks came from eastern Anatolia and not much earlier than 1600 BC, based on the belief that chariot warfare was invented there not much before that date.

- The finds were in towns, but not in anything like the high Bronze Age civilizations of the Middle East. I may have overstated the level of cultural and technical sophistication required to produce and maintain war chariots.

- The date isn’t anywhere near early enough to support any “Vedas before 3000 BC” theories. I still think some time after the collapse of the Harappan civilization, and shortly after the Indo-European chariot warrior conquests in the Middle East, is the convincing date for Vedic-speaking chariot warriors in the Punjab – i.e. after 1800 BC.

related entries: Yoga

all text and images © 2003–2008