|

|

|

|

Traditional Keralan Kathakali

|

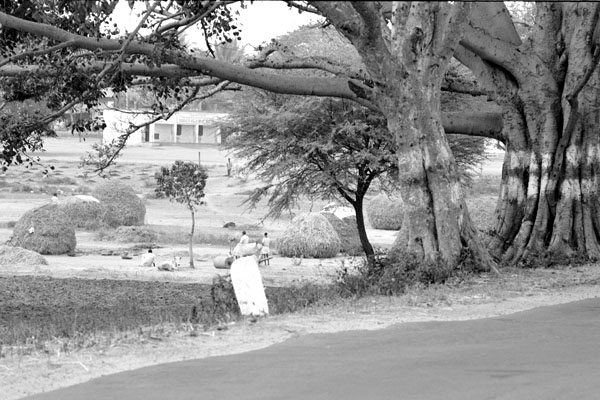

sacred cow, Gokarna

|

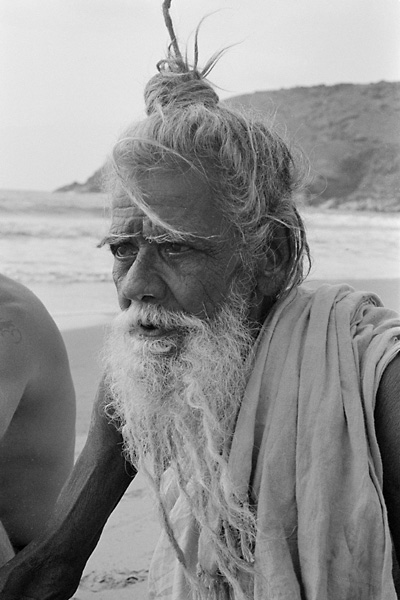

Sadhu (holy man)

|

The diamond-bright dawn woke men and crows and bullocks together. Kim sat up and yawned, shook himself, and thrilled with delight. This was seeing the world in real truth; this was life as he would have it - bustling and shouting, the buckling of belts, and beating of bullocks and creaking of wheels, lighting for fires and cooking of food, and new sights at every turn of the approving eye … and Kim was in the middle of it, more awake and more excited than any one.

Rudyard Kipling, Kim

This article is a practical guide to how to live, travel and take photographs in southern India, whilst trying to some degree to avoid the standard western tourist/traveller circuit and see things not every visitor sees. It is based on my photographic experiences on two separate visits totalling about six months - a month in Kerala in the winter of 1999/2000, and five months based in Mysore in 2001/2002. Both times I was mainly there to study yoga, but seeing something of the country and the culture and getting some decent pictures was also a high priority.

I've travelled fairly extensively in the states of Kerala and Karnataka and a little in Tamil Nadu; in all I've shot around a hundred rolls of film in India. Which, I know, is less than some working professionals shoot in a week - but still, enough time and film to have some idea of what I'm talking about.

I firmly believe that to get decent photos of a place, you have to spend time there and build up some empathy for whatever it is that's going on that you want to photograph - the people, the landscape, the light. If you want a list of obvious and clichéd photo-ops at well-known tourist destinations, that you can venture out to on day-trips from five star hotels whilst scrupulously avoiding any contact with the realities of Indian life and culture, and never getting dirty, sweaty, tired and thirsty, then this isn't what you're looking for. Unless you're an unusually brilliant photographer like Raghu Rai, it's highly unlikely that you're going to get a picture of the Taj Mahal that's going to impress anybody except your mother (and the Taj Mahal isn't in southern India anyway). But maybe, if you spend a week somewhere and get a feel for how the light falls at every time of day, you might get a picture of dawn light in the mist through a line of banyan trees, on a little country lane, that really is special for you and hasn't been photographed a thousand times before. I spent a large proportion of my serious photography time in India alone, photographing places and things I'd never heard of or seen pictures of before – a far cry from the tripod-wielding crowds in Antelope Canyon, or the throng of photographers at the Tetons viewpoint that Michael described on his trip to Wyoming. (Not that Michael's Wyoming pictures weren't lovely – and I know it shouldn't matter, a picture either stands on its own artistic merits or it doesn't; but I personally get more satisfaction from a picture of something that a photographer has found and seen for his or herself, than from yet another shot of somewhere like Antelope Canyon or Monument Valley)

I was fortunate to have enough time to get to know some areas, particularly the city of Mysore and its surroundings, fairly intimately. This meant I had a chance to get to know the sights and the light, and could spend days just wandering about with a camera well away from anywhere that tourists who just visit the city for a couple of days would ever see. I got a lot of my best pictures that way. I was even more fortunate to get to know a lot of people, both westerners and locals, who had spent a great deal more time in the area than I had and could point me to places and photo-subjects I never would have stumbled across on my own. One Indian friend in particular very kindly invited me to spend a week in his home village on the north Karnataka coast. This is a remote area, a long way from any major cities or airports. It is more than comparable in beauty to the better known beach resorts of Goa and Kerala, and almost entirely unknown to foreign tourists. My friend's grandmother said I was the first foreigner she had seen in her village - a beautiful farming village in the forest, less than a mile from some of the most spectacular empty beaches I have ever seen - for at least a year.

If that's the sort of thing you're interested in, I hope I might have something helpful to say. I will mention places that I found worth looking at and taking pictures of, but I'll talk more about the practicalities of living, travelling and being a photographer in South India, and where to look for, hopefully, some interesting and non-obvious pictures.

Most of the well known tourist destinations in India are in the north - Delhi, the Taj Mahal, Varanasi, Rishikesh, Rajasthan. The south, apart from the beach resorts of Goa and Kerala, is less touristy and it's easy to get off the beaten track. Kovalam, in the state of Kerala in the far south, is a busy, westernised, commercial beach resort full of foreigners (and, incidentally, a good “India For Beginners” venue for a first visit). Hire a motorbike and go two miles down the coast to the next village, and suddenly you're in India and you'll be mobbed by kids whenever you stop because, as a westerner, you're the tourist attraction now.

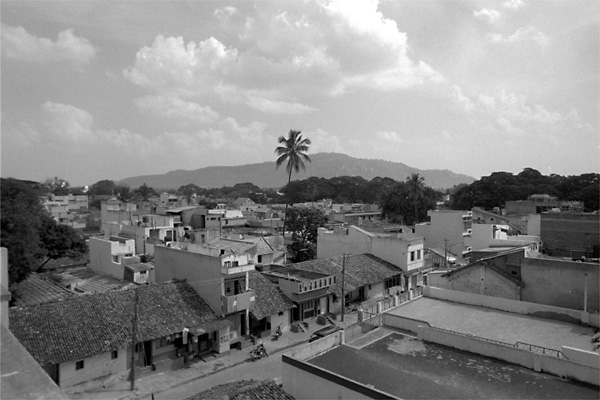

The southern states of Karnataka, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu are only home to about a quarter of India's total population, but they are proud of their distinctive culture and their relatively prosperous and peaceful society. South India is quite different in language and history from the north. The south is relatively (although by no means completely) free of the Hindu-Muslim tension and inter-caste conflict of the north, and significantly more prosperous - Bangalore and Hyderabad, state capitals of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh respectively, are India's high tech boom towns. One farmer I stayed with proudly told me that the state of Karnataka has fibre optic to every village – this while I was struggling to troubleshoot his incredibly slow internet connection that had to make its way down the mountain on five miles of copper wire before it could hook up to the fibre optic connection in the village. In Mysore, on the other hand, I maintained my online diary at an internet cafe run by the city's main ISP, on the fastest link I've ever used anywhere.

People in the south speak Dravidian languages that belong to a different family from the Indo-European languages of the north. The south has millenia of continuous undiluted Hindu culture – unlike the north, it wasn't conquered and ruled for centuries by Muslim invaders from central Asia. The hand of the British rested relatively lightly here, too - the “Madras Presidency” was a backwater of the Raj from the early nineteenth century onwards; unlike in the north, the army of Madras didn't rise against the British in the Mutiny/War of Independence of 1857. Large areas of present day Kerala, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh continued to be ruled by semi-independent Indian princes – Gandhi had the highest respect for the Maharajah of Mysore as a ruler (he was also the patron of some of the most influential yoga teachers of the twentieth century, and as such was arguably partly responsible for the survival and current popularity of yoga practices). His ex-subjects in the state of Karnataka still have great affection and respect for their former king.

If you are, or would like to be, a connoisseur of hindu temple architecture; if you think epic bus journeys to one-horse towns in the middle of nowhere that happen to have historically significant temples could be just the way you want to spend your vacation; then Lonely Planet South India is the book for you. Buy it, read it, be awestruck by its authors' dedication to the cause. Even if, like me, you decide you don't really want to make a full time career of it, a certain amount of temple-visiting will be an almost inevitable part of your Indian vacation / photo tour. Here are the basics.

Guidebooks (such as Lonely Planet South India) will tell you that there are many types of temple which can be classified according to things like the presiding deity - Shiva (Shaivite) or Vishnu (Vaishnavite); or according to historical periods or architectural styles - Chalyuka, Hoysala, Vijayanagar.

In reality, for the ignorant photographer-tourist there are two types of temple that matter.

There are those where you will be incessantly hassled from the moment you come anywhere near the place for “offerings” and “guides' fees” for somebody who tells you some piffling piece of information about one or two statues whether you ask them to or not. Your chances of actually finding a decent vantage point or a moment's peace and quiet to compose a picture in such places are minimal. The temple on Chaumundi Hill in Mysore is a prime example of a temple of this kind, as is the Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple in Trivandrum, the state capital of Kerala.

And then there are ones where, after you have penetrated a thin screen of postcard and souvenir sellers, you are left alone once you are in the temple precincts. You actually have time and peace and quiet to really look at the place and photograph at your leisure; and if you have chosen to employ the services of one of the guides, you find that they are genuinely helpful and knowledgeable. The 12th century Hoysala temples at Belur and Halebid, with their amazing sculptures, are very much in this category and make for a long but worthwhile day trip from Mysore or Bangalore. Also in the same area, and well worth a visit, is the Jain holy site at Sravanabelagola, home of what is said to be the world's second largest stone statue (the largest, apparently, being one of Pharaoh Ramses II in Egypt).

I've been to the three biggest and most famous Hoysala temples at Somnathpur, Belur and Halebid, which are all Indian national heritage sites - but there are dozens of smaller ones that are probably also beautiful, interesting and with even fewer tourists. Dr Prabhu, proprietor of a pro lab in Bangalore who is always keen to chat to serious visiting photographers, took the pictures for the definitive multi-volume monograph on Hoysala architecture; I'm sure he'd be willing to point people to interesting spots off the beaten track.

Temples often have rules and prohibitions that affect the photographer/tourist. Some, particularly in Kerala, are closed to non-Hindus. Some, like the amazing thousand year old Sri Ranganatha temple at Srirangapatna near Mysore (a must-visit if you are in the area), welcome visitors but ban photography. And some – mostly ones that are run by the state as ancient monuments – allow photography but ban tripods. This last ban is mainly aimed at preventing film crews from setting up shop in ancient temples and national parks (or extracting large sums of money from them for the privilege). The rules are sometimes, unoffically, negotiable, particularly if you manage to arrive on a quiet day when the place isn't teeming with school parties.

Tibetan Buddhist temples are also well worth visiting. One of the largest Tibetan refugee settlements in India is just outside Mysore: when I visited in 2001 they had two spectacular temples, and the Dalai Lama opened another one in 2002. The murals and artwork are fantastic, and the monks' approach to visitors with cameras is completely laid back - a total contrast to the frenetic atmosphere and photographic restrictions that are part of any visit to a Hindu temple.

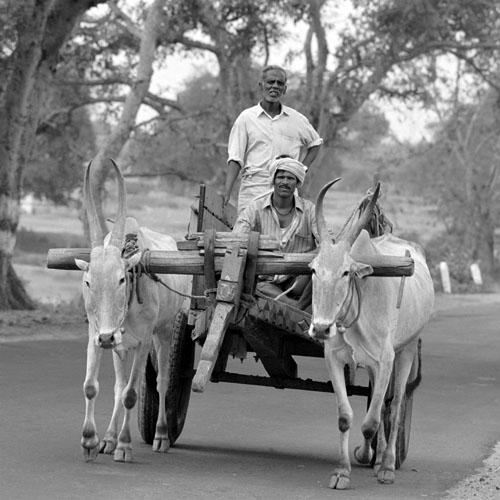

Travelling is just as much a part of the Indian experience as arriving at destinations, and the photographic potential on Indian highways is spectacular. Two men and three goats on a single scooter - and this not on a remote country road, but in the middle of the city of Mysore - or an entire family of four or five. Shoolchildren crammed ten or twelve to a rickshaw. Painted trucks with the entire front draped with flower garlands. Bullock carts everywhere, even on the elevated expressway in the middle of Bangalore, India's high-tech metropolis. Working elephants, wild elephants. Roads shaded by avenues of huge ancient banyan trees, with striped orange evening light or morning mist between the trunks.

It's all quite tricky to photograph, though. My attempts at pictures from moving vehicles had limited success (perhaps a case where a modern camera with fast autofocus and fancy metering would have had the edge over my all-manual outfit); and setting up a tripod by the side of a major road attracts loads of hassle from curious onlookers, not to mention the fact that doing anything that distracts your attention from pure survival, anywhere near Indian traffic, is hazardous. Remote country roads are ok, so is early in the morning when there isn't so much traffic about.

Southern India doesn't have big mountains, deserts or any world-famous clichéd landscape photo locations. In a way this is a plus – it means you have to find your own pictures, pay close attention to the land and the light. You can't just try to copy what other people have photographed before you. But there are still interesting landscape pictures to be had.

People in India may look, speak and dress differently from people you know at home, and probably have less money on average – the key thing to always remember is that being different and poor doesn't make them into exhibits in some kind of human zoo. Respect and politeness are crucial. You should always be absolutely clear about getting a stranger's permission to photograph them and if they seem in any way uncomfortable or unwilling, don't. Steve McCurry talks about how to go about getting permission and establishing rapport with people, even when you have no common language or culture, in this interview for Outdoor Photographer.

Kids are a completely different matter. Schoolchildren will come running and clamour to be photographed whenever they see a foreigner with a camera. The easiest way to get rid of them is to take a picture or two – if for some reason you don't want to (a couple of times, for instance, I wanted to shoot a whole roll on the same theme for a contact sheet) you will have to be firm and patient to get rid of them. Or be careful to shoot during school hours.

Big Indian festivals are famously photogenic, but I can't comment on this from first hand experience because I seem to have a talent for missing them. I arrived in Mysore at the end of October 2001 – a week after the city's Dussehra festival, famed for its elephant parades and mass festivities. I went travelling in Kerala in mid-January – Kerala being the only state in the south that doesn't have a big harvest festival in mid-January. In Mysore, where I would have been if I hadn't gone to Kerala, they round up all the cows, paint them bright yellow and then parade them through streets lit with huge bonfires. I was in Gokarna, the most important pilgrimage centre in south India for Shaivites (worshippers of the god Shiva), in March 2002 a few days before Maha Shivaratri, the biggest religious festival of the Shaivite year … and had to leave to get my flight home.

Jean-Pierre Verbeke clearly doesn't have the same problem, judging by his stunning pictures on photo.net of Kumbh Mela, a huge hindu religious gathering that takes place every few years on the banks of the Ganges. If you do find yourself at such an event, it is absolutely essential for your own safety, and more importantly out of respect for the dignity and privacy of the worshippers, to always make sure you get permission to take pictures and observe any bans on photographing important religious occasions.

Hampi is rapidly becoming the most famous tourist attraction in southern India; and although I'm generally in favour of getting off the western tourist trail and taking enough time to find your own places and things to photograph, it is a must. It is one of the most amazing places I have ever seen.

Five hundred years ago Vijayanagar - the city that once stood where all that now remains is the little village of Hampi - was the most impressive city in India. It was the capital city of a Hindu empire that ruled the whole of the south, and had held off the Muslim invaders from the north for centuries. Eventually the Hindus were defeated, and the city was sacked by the Muslims and abandoned. All that is left now is miles and miles of a fantastically harsh and beautiful landscape of steep little hills covered with huge granite boulders, dotted with literally hundreds of ruined temples - some of them very impressive indeed - with a couple of scruffy villages huddled in the ruins.

Hampi itself is a pleasant enough place with a well-developed traveller/tourist scene. The photo opportunities in and around the ruins are limitless. I particularly recommend sunrise or sunset from the temple on top of Matunga Hill, which is a steep little hill overlooking the eastern end of the village. Getting up there for sunrise is a challenge – it would be a good idea to reconnoitre the path in daylight beforehand – but the views are worth it. (The local police point out that the ruins in general, and Matunga Hill in particular, are a hotspot for muggings of tourists. Lone tourists with expensive cameras are a particularly obvious target, so going up there on your own in the dark, as I did, probably isn't such a great idea. Good luck trying to persuade your travelling companion(s) to get up before 5 in the morning and go hillwalking by moonlight.)

“I do not think there is a more interesting or beautiful view than this, in the whole of Southern India”

A.H. Longhurst, Hampi Ruins Described and Illustrated (1917)

By this time the sun was driving broad golden spokes through the lower branches of the mango trees; the parakeets and doves were coming home in their hundreds … and shufflings and scufflings in the branches showed that the bats were ready to go out on the night picket. Swiftly the light gathered itself together, painted for an instant the faces and cartwheels and the bullocks' horns as red as blood. Then the night fell, changing the touch of the air, drawing a low, even haze, like a gossamer veil of blue and bringing out, keen and distinct, the smell of wood-smoke and cattle and the good scent of wheaten cakes cooked on ashes.

Rudyard Kipling, Kim

India is in the tropics where dawn and dusk happen very quickly. You have about half an hour of very rapidly changing golden light morning and evening, enhanced by the red dust that always hangs in the air in the dry season, then it's gone - full daylight or full darkness, almost instantly. Sometimes in the “cold” season, morning mist prolongs the interesting morning light for an hour or two. This generally means that by the time you've seen something interesting, registered it and set yourself up to try to take a picture of it, it's gone. I was on the main road from Bangalore to Mysore one evening, and we came to a long downhill avenue of huge banyan trees growing over the road, with beams of orange light between the trees picking out the traffic coming the other way up the hill. By the time I had my camera out and had thought of asking the driver to stop, the sun had dropped behind the hills and it was all over. So then you need to be in the same place again at the same time the next day, tripod set up, ready and hoping for the same light; which therefore argues strongly against too much rushing from place to place trying to tick off everything on some kind of mental checklist of photo-ops. Good.

What type of equipment to bring depends on: what you have or can afford (obviously); what type of photographs you think you want to take; and in what style you intend to be living and travelling.

If you definitely want to do serious landscape or wildlife photography, then obviously you'll want to bring the biggest tripod you are willing to carry plus one or more Big Cameras and/or Long Lenses. Which adds up to a lot of stuff to lug around with you, but presumably you're used to it and think it's worth the hassle. If you want to do more travel-reportage, street and people photography, then a good 35mm camera and a small selection of lenses will be a lot easier to live with. Remember that guys like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Raymond Depardon travelled all over the world getting better pictures than most of us ever will, with a single Leica and one or two lenses; Indian photo legend Raghu Rai says he almost always works these days with a single Canon body and a zoom lens.

Whatever you bring, any serious photographic gear will really make you stand out from the crowd even more than you already do as a foreigner. In all the time I spent in India on both trips, including photographing some major tourist destinations, I didn't see anybody else shooting medium format; I did see a couple of tripods strapped to backpacks but I never saw anybody else actually using one.

I travelled with a Nikon FM2 body and four lenses from 24 to 180mm, a Fuji 690 medium format rangefinder and a Velbon carbon fibre tripod, which was about the limit of what I was willing to carry. A longer MF lens would have been nice for landscape work, but the weight and bulk of the lens plus a bigger tripod would have been prohibitive for the kind of travelling I was doing. The FM2 and the Fuji are both ideal travel cameras - excellent quality, compact, robust and almost no risk (absolutely no risk with the Fuji) of battery problems when you're miles from anywhere. I also took a Yashica T4 to carry around as a pocket camera, but actually found I didn't use it much.

If your cameras need more by way of electrical power than mine did, AA and other common battery sizes are available everywhere (but note that Indian airline security folks have a wierd fetish about not allowing batteries in hand luggage), as is mains electricity most of the time, although power outages are common (see below).

You probably won't be backpacking far off the beaten trail in southern India. The trekking opportunities aren't that great - most of the spectacular hilly landscape in the western ghats is severely threatened by population growth, deforestation and encroaching development, and much of what is left is locked up in national parks with severely restricted access. Anybody who wants to do serious mountain trekking in India would go to the Himalayan states, not the south. On the other hand, if you have the time to arrange trekking permits and/or book local guides, there are worthwhile shorter treks to be done in the remoter parts of the western ghats. The Lonely Planet South India guide has contact details for some recommended trekking agencies in Bangalore.

Even if you won't be doing any serious trekking, if you intend to be travelling on public transport a lot some of the same considerations for choosing gear apply. Indian buses and trains are almost always crowded & don't have much luggage space, and trying to negotiate them with more than one bag is a struggle. So if you're planning to be travelling most of the time, you need a photo outfit that will fit in one backpack with enough spare room for whatever else you want to carry with you. If you plan to base yourself somewhere and do excursions, it would still be good to have a camera bag that was big enough for all the equipment and film you think you'll need for any likely outing, plus washing gear, change of clothes, mosquito net, water bottle and a book. Mine wasn't, which meant I had the major hassle of dealing with two bags whenever I went anywhere for a weekend or more.

There are two schools of thought regarding getting film processed while travelling. One is horrified at the thought of risking their precious images in the hands of a lab they don't know and trust. The other is horrified at the thought of risking their precious images in the hands of airport security or any postal system. I personally tend more towards the latter view; unfortunately there is a strong case to be made for both in India. Airport security is rigorous because of years of Kashmiri terrorism – you have almost no chance of geting film through without it being x-rayed and hand-searched at least once, and the x-ray machines probably aren't the most modern or best maintained in the world. And the quality of local film processing is, well, variable.

I personally have a greater horror of film in airports than of using unknown labs; I also like to see what I'm doing as I'm going along so that I can learn from it, especially on long trips. So I tried to get as much film processed locally as possible, having first done my research on photo.net and got some recomendations for decent labs.

It's worth bearing in mind, even if you use some other medium for your "serious" pictures, that it's handy to shoot some 35mm colour prints that you can get processed quickly & easily for giving to friends that you've met along the way. You can meet interesting people that way - I took a picture of some kids in the street near where I was staying in Mysore that came out well, so I thought I would take a print round to the house as a gift for the family. Their father was delighted, we got talking and it turned out he was a well-known choreographer who does a lot of film and fashion work. He invited me to a show that he had coming up a couple of weeks later, which I'm sure would have been fascinating but it was after I left town (so sadly no pictures of drop-dead gorgeous Indian fashion models)

Whatever your view on film and airport security, it's probably a good idea to try to bring a few weeks' working stock with you. I arrived for my second trip with about 30 rolls crammed into corners of my camera bag, which was a lot of grief with hand searches and worrying about x-rays, but it all came through unscathed, even the NHG II, and it kept me from having to worry about local supplies for a few weeks. If you know you will have a stable base address in India, getting film mailed to you from your favourite home supplier might also work; but I personally have no experience of doing this and know nothing about the risks, either of severe delays in Indian customs or getting your film damaged.

When you do run out of the film you brought with you, if you are anywhere other than a big city you have a problem. Even in Mysore - a city of almost a million with a couple of reasonable minilabs - I saw nothing anywhere but the tackiest of tacky 35mm consumer print film. A minilab place somewhere like Mysore probably at least keeps their tacky consumer print film cool and sells it quickly – whereas if you're out at some little kiosk out in the countryside, who knows how long the film's been sitting in the sun? Your only real hope is a professional lab in a big city, and there are only two cities in southern India with big enough photography markets to support decent professional labs - Bangalore and Chennai (formerly Madras). A couple of places that I can definitely recommend in Bangalore are Prabhu and R.K. Photo, both of which stock a wide range of Kodak and Fuji professional film in 35mm and medium format. I've never been to Chennai so I can't personally recommend anywhere there - there are some recommendations in the photo.net discussion thread linked to above.

If you do decide to get processing done locally, the same basic cautions about choosing a lab apply just as strongly in India as they do anywhere else - talk to the owners and staff and see if they seem enthusiastic, knowledgeable and professional; talk to other people who have used them, either other serious travelling photographers or, ideally, local pros and look at examples of their work; get them to do a few not-too-important rolls of snapshots first before you trust them with what you hope are your classic works of art.

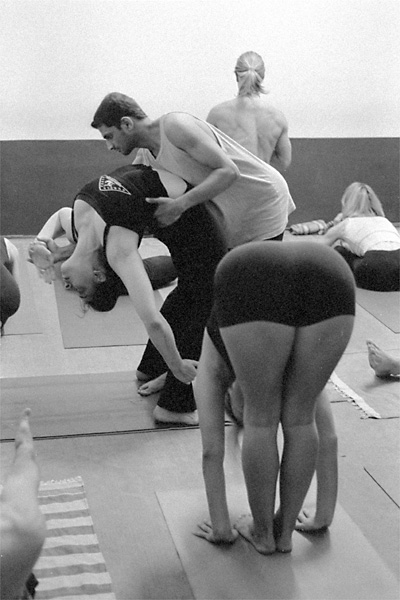

With regard to film, whether you bring it with you or buy locally, I'll assume that you already know what you like for general everyday shooting. The only point I will make is that it's a good idea to have some fast film. Indian architecture is mainly designed to keep direct sunlight out and keep places as cool as possible, so interiors are dark. Even the (very photogenic) city market in Mysore, although it's open air, has narrow passages with thick awnings over them and shooting handheld with 400 film just wasn't working for me; I had to go up to NHG II at 800. I also wanted to get some pictures during class in the yoga school I was studying at in Mysore. Classes started before dawn, the room light was very dim fluorescents, using flash was out of the question and there was no room to set up a tripod. Prabhu in Bangalore saved the day with a couple of rolls of TMax 3200, which came out surprisingly well shot at 6400. My preferred fast films are TMax 3200 for black & white, and Fuji NHG II or NPZ for colour. It's a good idea to have a few rolls of these or something similar with you – but of course they are the very films that you really don't want to be taking through airport security. They are obtainable locally, but only at the major film stockists in the big cities.

Indians mostly use fluorescent lights because the running costs are lower than incandescents, so if you're doing a lot of available light interiors you might want to think seriously about using black & white. Otherwise you'll be spending a lot of time in Photoshop trying to correct pictures that look like they were taken at the bottom of ponds. Black & white in India is problematic, though. Ilford is practically unheard of so if, like me, your favourite general-purpose b&w film is XP2, make sure you bring lots of it and don't run out halfway through your stay (like I did). The minilabs I used in Mysore did a decent job of producing XP2 proofs, making considerable efforts to get them to look reasonably neutral on colour paper. The conventional b&w processing I had done, on the other hand, ranged from ok to unbelievably awful.

This reflects what seems to be a general Indian lack of interest in black & white as a medium. People just aren't impressed by black & white photographs - they want colour. I took some pictures of a temple stonecarver in his workshop in Mysore. I was pleased with them, so a few days later I went back to give him some prints. His reaction wasn't the "oh thank you, what great pictures" that I was hoping for, it was a disappointed look and "oh, black and white".

A couple of weeks later I was staying with an Indian friend who wanted me to do some portraits of his grandparents. Remembering the incident with the stonecarver I said yes, fine, by the way I've got black & white film in the camera at the moment, is that ok? He insisted that I switch to colour and, as it was an important occasion and the client is always right, I used up my last precious roll of Reala. One last example – as I was leaving the country, I spotted a book of Cartier-Bresson pictures of India in the bookshop at Bangalore airport. It was on the top shelf so I asked the shopkeeper to get it down for me. Oh no sir, you don't want to look at that – it's all in black & white, why don't you look at this book of colour pictures by [some guy you've never heard of who almost certainly isn't one of the great artistic geniuses of the twentieth century] instead?

So if you want to shoot black & white, bring your film with you; save the processing until you get home; or if you do choose to get processing done locally, still don't expect to impress your new Indian friends with your Cartier-Bressonesque immortal masterpieces.

It may sound like film and processing in India are major hassles, and they are. I don't shoot digital (yet), but I imagine doing the kind of travel photography I like to do in a relatively undeveloped place like India would bring with it its own set of hassles and tradeoffs using digital. Power supplies can be sporadic; I know I would find travelling with a laptop a major burden; and without a laptop I wouldn't even want to think about how much enough microdrives to replace a backpack full of film would cost. Not to mention the problems of backing them up, or the risk of having all your precious images on a few tiny cards that could easily be lost, stolen or damaged. For me, the cost / portability / reliability equation for travel photography still seems to be in favour of film.

In most of southern India you and your equipment are probably safer than in a "bad" part of almost any major city in the West. The further off the beaten tourist track you get, the more polite and friendly people generally are. There is a problem with theft and muggings in tourist areas, though. I did most of my travelling alone and never felt seriously threatened carrying gear around or setting up my tripod and taking pictures (conspicuous yes, but not threatened). I did take try to always keep my gear locked up when I left it in my apartment or a hotel room, though - the Pac-Safe, a kind of wire mesh bag with a security cable attached that you can padlock to something, is a useful device for this. The mesh on the Pac-Safe is fairly coarse, though – I now have a nice little hole in my camera bag, where I left it with some sweets in an outside pocket, chained to balcony railings in my hotel room within easy reach of the local monkeys.

Any travel guidebook will give you advice about what clothing, medical supplies etc. you need for travelling in India. I'll just point out a couple of items that I would never travel without. Power outages are an almost-daily occurrence everywhere in India, even in major cities. Even if you don't choose to go for pre-dawn cross-country hikes, it's a good idea to have a small torch (flashlight) with you. I carried a small twin-AA maglite which was invaluable. I also had one of the tiny single AAA-cell maglites on my keyring that got me out of trouble on a couple of unplanned hikes in the dark. Malaria risk is generally low in southern India, with the important exception of Hampi – but even so, mosquitos are everywhere and a mosquito net is the only way to get a quiet night's sleep. You can buy cheap ones locally, but they're not insecticidal and they're too bulky for travelling with a backpack. Better to bring a good lightweight one with you from home.

India has nineteen official languages; estimates of the number of languages actually spoken, including obscure tribal dialects in remote areas, range into the low thousands. English is fairly widely spoken as a second language and southerners are one of the main influences in favour of keeping it as an official national language, partly because they don't want the country completely dominated by Hindi-speaking northerners, and partly because their growing prosperity depends on being able to work with English-speaking partners in high tech industries. This is just as well for western travellers, because each state has its own language and its own script, and the languages are completely unrelated to English. Unless you're very linguistically adept your chances of learning a useful amount of even one of them on a short trip are almost nil. Even if you learn enough in one state that you can just about read where a bus is going, as soon as you go to the next state you're illiterate again. So it's fortunate that you can get by in English pretty much everywhere for practical matters like buying food and finding places to stay – but don't expect to be having too many profound conversations, outside the major cities the amount of English people speak and understand is very limited.

India is a tropical country, with levels of hygiene and sanitation significantly below what we're used to in the west. All the usual precautions about immunisations, malaria, food & drink hygiene etc. apply, and are described in detail in guidebooks. Most western visitors, no matter how careful they are, have some stomach trouble in the first few weeks; I found that once I got through that, I was acclimatised and could pretty much eat what I wanted, even including railway and bus station food.

Most south Indian Hindus are vegetarian, and they have arguably the best vegetarian cuisine in the world. Even if you're not vegetarian at home it's probably far safer not to eat much meat in India, and the local veg food is unlikely to disappoint you. This is especially true if you stay or get invited to eat with a family – home cooking tends to be better than restaurant and cafe food.

It is very rude – for reasons to do with hygiene & sanitation – to eat or to pass anybody anything with your left hand. It's also normal to take your shoes off before you go indoors – this is important if you get invited into anybody's house, and essential when you visit temples. It's also important for western women to wear clothing that covers legs and shoulders, not only out of politeness but also, unfortunately, to minimise hassle from some Indian men.

Southern India has three seasons – winter, summer and monsoon. The high season for western tourists is winter – around November to February. “Winter” temperatures are pleasantly warm and mild by European / North American standards – generally around the high 20s celsius inland, significantly warmer on the coast and cooler in the hills. Early mornings are a cooler, but except in the hills you'll never need more than a light sweater and usually not even that. Night-time temperatures in the hills can occasionally drop to around freezing, but it never snows – winter is also part of the dry season.

“Summer” – around March to June – is significantly warmer, maybe mid-to-high 30s celsius; but (I'm told) not as extreme as in northern India, where winter is cold and summer on the plains is brutally hot. The third season is the monsoon, which comes in two parts – the south west monsoon in July & August, and the north east monsoon in September & October. Because of the direction of the prevailing winds, the former is more intense on the west coast and the latter on the east coast. In the monsoon it rains. A lot.

Most of my time in India has been in the winter, although on my second visit I caught the tail end of the monsoon in October and stayed until the beginning of summer in March. I hope to make my next trip at the end of summer / start of the monsoon; there are very few tourists around at that time of year, and from what I saw at the end of the monsoon last year, the potential for landscape photography in the hills and on the coast should be spectacular, with fantastic watercolour cloudscapes after the rain. On the other hand, travel at that time of year could be a challenge. Roads and railways are disrupted by flooding and landslides. Sanitation becomes a major issue. A lot of hotels, restaurants and other tourist facilities are closed outside the high season – a large proportion of tourist businesses in the south are run by northerners from Kashmir and Rajastan, who go come south for the winter and go home for the summer. And I expect the challenges of keeping cameras and film dry will be non-trivial – definitely not somewhere for Michael to take his delicate and expensive electronic Rollei kit, although I imagine a 1Ds would be ok.

Planes, trains & automobiles. And buses, rickshaws, motorbikes, scooters & bicycles.

Even if you take the (correct) approach of basing yourself somewhere for long enough to get a feel for the place and what photo opportunities it has to offer, rather than rushing from one tourist hotspot to another, trying to “see” everything and experiencing nothing – nevertheless from time to time you're still going to want to go somewhere that's further than walking distance from wherever you're staying.

For travelling from A to B over long distances, your options are planes, buses or trains.

Domestic flights in India, operated by Indian Airlines and Jet Airways are frequent, reliable and reasonably priced. If you want to get somewhere a long way away, quickly and with minimal hassle, flying is definitely a good bet. On the other hand, you're missing out on aspects of the Indian Experience, and corresponding photo-opportunities, that you can get travelling by other means.

Long distance buses come in two varieties. State buses are cheap, generally reliable, but very basic and uncomfortable. Sometimes you get glass in the windows, but never padding on the seats. The drivers are generally maniacs. Private “luxury” buses, which I personally never bothered with, are much more expensive and have padded seats, sometimes air conditioning and sometimes unbearably loud hindi musicals on video. The drivers are generally maniacs.

Buses are almost always crowded and have very little interior space for luggage - travelling with anything more than one moderate-size backpack is a major hassle.

Nevertheless, long distance buses are a viable and – if you can keep an open mind about a bit of discomfort and fear – interesting mode of travel. Local buses are another story altogether. People who speak a useful amount of English are few and far between in remote rural areas so if you can't speak the local language, or at least read the names of towns, even getting on the right bus would be a lottery. Even if you do manage to get on the right one, local buses are even scruffier than long distance buses, are often dangerously overcrowded and have even more manic drivers. All of which can still make for an interesting day out if you're travelling with a knowledgeable local, but probably best avoided if you're not.

Trains in India are cheap and reliable, but slow and crowded. It's generally a good idea to book seats in advance, and absolutely essential to book sleeper berths if you're travelling overnight. The ordinary second class sleeper carriages are spartan but I found them perfectly ok; if you want a bit more comfort and privacy, various first class and air-conditioned options are also available on some trains. India is a big country and the trains travel slowly, so you need to be mentally and physically prepared for long journeys with not much by way of comfort. Food and drink (very sweet and milky tea or coffee) are sold on the trains – but unless you've been in the country for a few months and your digestive system is well acclimatised, it's probably a good idea to bring your own supplies. Long distance trains have occasional long stops for half an hour or so at major stations, which are an opportunity to stretch your legs and stock up on bottled water and newspapers, assuming you know when you're going to have time – study the timetable carefully or ask your neighbours.

For day or weekend excursions, hiring a car and driver is common practice (self-drive car hire is unknown and believe me, on Indian roads you don't want to anyway). If you go to a decent travel agency and ask for a “jeep”, you will get something SUV-sized that will take four or five passengers with gear in comfort, up to eight people absolute maximum. An alternative is to just negotiate a daily rate with a taxi driver, which costs almost the same but you get a cramped, less comfortable and reliable car with more “local character”. I made one day trip from Mysore in a taxi; we had two breakdowns in the course of the day. The first was just a puncture. The second was more exciting – the brakes failed and we had to drive brakeless to the next village to buy new pads. Go for the jeep. Either way it will cost you around 30 US dollars a day total – way more than buses, but really not an issue if you're splitting it four or five ways, unless you're travelling on a very tight budget indeed. The driver will usually stay with the car at all times, so the security of any gear you're not using isn't a problem. Unlike a bus or a train, where you go and when is entirely under your control – the driver will go wherever you ask and stop whenever you want to. I used Bharath International Travel in Mysore regularly and found them good. Their prices aren't rock bottom but their drivers are consistently excellent – safe, friendly and knowledgeable, with spotlessly clean and reasonably new cars. If you're happy with your driver, a decent tip on top of the agreed price is definitely in order.

A more adventurous option is to rent a scooter or a motorbike. I did this the first time I was in Kerala – a friend and I rented Enfield Bullets (Indian-made copies of classic 1950s British bikes) and headed up into the hills for a couple of days. For me it was one of the best parts of my first visit – getting away from tourist India onto the rural backroads of the Real Thing. But the risks to both you and your gear should be obvious: you're riding an unfamiliar and possibly poorly maintained vehicle, on some of the world's most dangerous roads, without a helmet or any other protective gear. On our Kerala trip my friend Jeffrey was knocked off his Enfield by a drunken local on another motorbike, and was lucky to get away with a badly bruised ankle and a broken clutch lever. Another couple I knew were chased by a wild elephant.

Tony was an English biker I met in Hampi. He had ridden his BMW out from England, and hoped eventually to make it to Australia |

If you decide to try out the motorbike option, it's a good idea to plan your routes to avoid major state and national highways as much as possible. Not only do you get to see more countryside and village life that way, and more chances for little surprise out-of-the-way photo opportunities; but more importantly, you get to avoid being constantly bullied, intimidated and shoved off the road by hordes of manically-driven, fume-belching long distance buses and trucks.

Scooters are cheaper to rent than real motorbikes, and a lot easier to ride if you don't have motorbike experience. I rented one when I was in Mysore and found it great for getting around town, and just about ok for short day trips out into the countryside. For anything further, the riding position on a scooter is just too uncomfortable and you need a proper motorbike. Petrol in India costs about the same as it does in Europe (i.e. is shockingly expensive by American standards).

Travelling after dark on Indian roads is stressful even if you're in a car with a good local driver, and outright terrifying if you're on a motorbike or scooter. You should avoid it unless you have a very good reason (it's up to you to decide whether wanting to take sunset photos somewhere further than walking distance from your base constitutes a “very good reason”) (pre-dawn isn't as bad, there's generally not much traffic early in the morning).

Hopefully sooner rather than later, your chosen vehicle-of-whatever-kind will get you to somewhere where you want to walk around and take pictures. As a westerner walking around anywhere in India, particularly with an obviously-expensive camera and even more so if you start setting up a tripod, you will constantly be accosted by children wanting be photographed and practice their English on you. This is generally quite cute, but gets wearing if you are feeling ill, tired or depressed and grumpy for any other reason – in which case ignoring them generally works. If you are anywhere near anything commercial or touristy, you will also often be mobbed by sellers, touts and beggars. Your policy towards beggars is up to you; sellers and touts are nowhere near as easy to ignore or get rid of as schoolchildren.

Any city or tourist area will have an abundance of cheap hotels. You have to shop around for somewhere clean and quiet, but around 200 to 300 rupees (5 or 6 US dollars) a night can get you a double room somewhere basic but decent. Expect to pay about double in very touristy areas like Goa or the Kerala coast in high season (December - January). I spent 3 weeks quite happily in the Kavery Lodge Hotel in Mysore - a clean, friendly place that is always busy. The clientele is about two thirds western yoga students, a third Indian businessmen. If you're spending time in rural areas off the beaten track, accommodation options can be severely limited, and you will have little choice but to put up with whatever the village guesthouse has to offer. Places with any pretension to tourism also often have a government-run guesthouse - these are generally pretty spartan, but clean and ok for a night or two.

If you're staying a few weeks in a major tourist area, it's worth looking into the possibility of renting a room with an Indian family. Rooms are basic but cheap, and you get to see at first hand how an ordinary Indian family lives. Superb home-cooked lunches are often included in the deal, as is free local insider knowledge.

Major cities and tourist areas have upmarket western-style hotels, ideal for those who want to avoid actually experiencing anything Indian during their stay. Some of these are in amazing buildings and locations - former maharajahs' or colonial governors' palaces – and they are probably considerably cheaper than equivalent places in the west, but I can't talk about them from much first hand experience. I stayed in a couple of semi-upmarket (50 dollars a night) hotels in 17th century Dutch colonial merchants' houses in Kochin, and the surroundings were certainly very nice, but I found them less friendly than a lot of cheaper places I stayed in.

Lonely Planet has guidebooks to South India, Goa and Kerala. I made heavy use of the South India volume. I also had a brief read of a friend's copy of the Footprint guide, which at first sight looked better. These have lots of sound practical information, but suffer from the fundamental paradox of all guidebooks for the “adventurous” traveller - if you follow them too slavishly, they will lead to you just following all the other western tourists around. Better to use them to get yourself established in an area, and then try to find out about interesting things to see by word of mouth, or just by walking or riding around.

There is (or was) also a German language guidebook, AP Fotoguide Südindien, which concentrated more on describing south Indian art and culture than on travel practicalities and had excellent photographs. Unfortunately it seems to be out of print. I saw it in the guesthouse I was staying at in Hampi, and thought of making the owner an offer for it but didn't; then wished I had when I got back to Germany and couldn't find a copy anywhere. Maybe it will still be there at the guesthouse in Hampi when I go back one day.

I kept an online diary during my second trip to India. There's a lot in it about my yoga studies, but also quite a bit about the practicalities of living, travelling & photographing in India. I also have India photo galleries in colour and black & white.

Alan Little is an expatriate Englishman who lives in Munich, Germany, and works as a software developer to fund his photography and yoga studies. He has a photo-article on “Sacred Landscapes of India” due out in the first issue of Nama Rupa, a new magazine on yoga and Indian philosophy. Alan's website is at www.alanlittle.org, and he can be contacted by email at contact@alanlittle.org

Text & photos © 1999 to 2003 Alan Little